Compiled by Mrs. Rita McCormick Bishop

BIOGRAPHY OF HARRY TERRY, M.D.

COUNTRY DOCTOR

Compiled by Mrs. Rita McCormick Bishop

(as presented in the Tampico Centennial Year Book 1875-1975)

To the four-year-old boy, seated in the high-back rocker in the corner of the living room, the flurry of activity surrounding him seemed difficult to comprehend. Yet, he knew that behind the bedroom door, now closed, his father laid ill. To the four-year-old boy, seated in the high-back rocker in the corner of the living room, the flurry of activity surrounding him seemed difficult to comprehend. Yet, he knew that behind the bedroom door, now closed, his father laid ill.

Slowly he began to realize that something sad and serious was taking place here. He felt that sorrow on his mother's face become a part of him and unshed tears began to sting his eyes.

Indeed, he had reason to weep on that May evening in 1882. Beyond that door, his father was dying. And with his passing, a woman would be left with three small children to raise alone.

Within the month after her husband's death, Mrs. George Terry took her young son, Harry, and his sisters, Grace and Elizabeth, to live with her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Matthews at Leon, Illinois.

Before Harry reached his fifth birthday,his mother enrolled him in the rual Leon School. Because he was so young, the teacher, a Mrs. Frank Howlett, permitted him to take naps during school time. He spent eight years in this little country schoolhouse. Learning came easily to him and he was an avid reader. The firmness of his grandparents and the devotion of his mother united in molding a character instilled with a sense of responsibility. This boy would never be content to only take what life had to offer, but rather would be obsessed with the idea of offering mankind all that he had to give. In later years, he would make those offerings again and again to physically sap his strength, but spiritually perfect a gentle man.

The farm was perhaps a mile from the school and Harry and his sisters walked the country road daily. He had one strange habit of which his mother could not break him. The scent of skunk delighted him and often he and his old dog, on the way to school, would rout a skink from its hiding place in hollow log or trunk of a tree to be rewarded by the indignant skunk with the desired all engulfing aroma. His sisters would run swiftly ahead, hoping to escape the sickening scent, but not young Harry.

Later, at school, the teacher would lead the class in the singing of America, only to have to stop at the end of the first stanza to haul the small child out of his desk and order him home to be bathed. This was such a common occurence, that his mother kept a large wash tub handy in the wash house so that both boy and dog could be readily dunked.

In 1890, he left the country school behind him. The high school was located in Prophetstown. This was a good distance from the little farm at Leon and so after much discussion, it was decided that Harry would board with the town doctor. Dr. Eskey and his wife would furnish Harry's meals and give him a sleeping room at the back of the doctor's office. In return, Harry kept the office cleaned and even helped the doctor on his cases when he could. In this environment and with the patience of the old doctor providing answers to his many questions, Harry began to think seriously of making medicine his career.

In his high school graduating class, he was the only boy. This was a time and an area when little store was set by schooling. It was more important for a boy to learn the rudiments of good farming or to get himself a job, than to while away his hours in a high school.

Needless to say, Harry was popular and sought after, but he had his eye on higher things, far off dreams of college and university, to be something, to rise above the crowd, to achieve a measure of greatness. He set his heart and mind on these goals and he never lost sight of the mark.

His mother knew that he should have this opportunity to further his education, but she was economically unable to assist him. His maternal grandparents, too, were not able to aid him financially.

He worked around Prophetstown at varying jobs for about two years after graduation. Meanwhile, his Uncle William, a bachelor living in St. Louis, offered to help Harry if this was his dream. William Terry had had a few dreams himself and plenty of ambition. He could well understand the driving force that pushed young Harry toward his goal.

Harry was enrolled in medical school at Washington University in St. Louis. He did not live with his uncle, but boarded near the school on Washington Avenue. He pursued the course of study with serious intent, taking odd jobs here and there to help pay his way. William Terry did not live to see his nephew achieve his dream. He died in 1902, but left provisions in his will that Harry would finish his education.

Harry's last year in school was the year of the St. Louis Exposition. The Exposition came about when, in January of 1899, the governors of the states that had been formed from the Louisiana Purchase sent delegates to a convention at St. Louis.

To a boy raised in the rural area of Prophetstown, St. Louis, at the turn of the century, was an exciting place to be. He found work that year of 1904 at the fair. It was demanding, but served to break the tension and monotony of that final year of study.

Upon graduation from the University, Harry interned at Berne, in St. Louis. Now he was really involved. All the years of work and study were beginning to be put to real and practical use. Life and death was here and more!

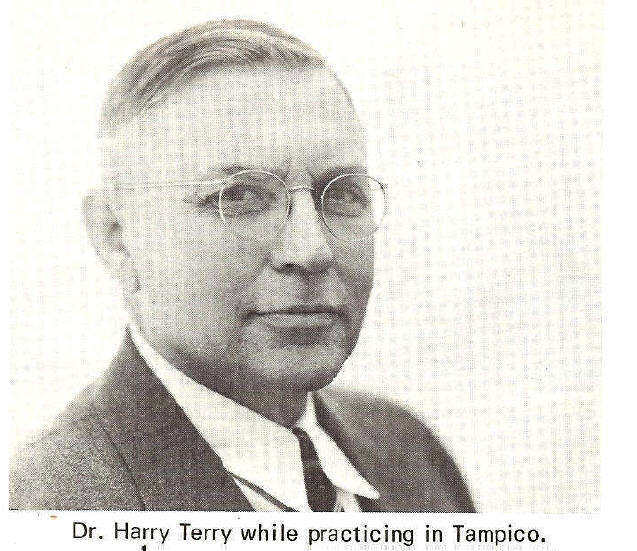

With internship behind him, Doctor Harry Terry came back to Tampico, a small village about ten miles east of Prophetstown, to begin his practice.

With an assurance born of the best available training, he began to birth the babies, set the broken bones, sew up the wounds and lend a sympathetic ear to these country people. To minister to humanity is in itself a nble undertaking, but when that humanity is composed of friends and neighbors, the satisfation of healing knows no bounds.

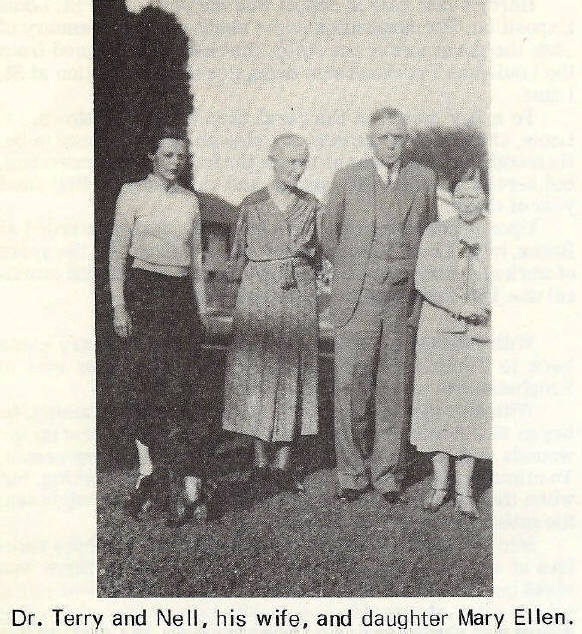

Into his life she came, as cool and lovely as all the heroines of all the books he had ever read. And yet, there was about her a wistful sort of sadness. Widowed, with two young sons to raise, she would not so easily be won. But, the young doctor was charming and he was persistent. His dark, brown eyes made her feel that perhaps life was really worth all the sorrow. He wooed her and he won her and on August 10, 1907, Nellie Aldrich Glassburn became the bride of Dr. Harry Terry.

Their world was alive with hope and promise. They moved into a house in Tampico, settled the two boys, Wayne and Harold, and began a rewarding life together. Later, in a year or two, they would make their home in a large apartment above his office. Their world was alive with hope and promise. They moved into a house in Tampico, settled the two boys, Wayne and Harold, and began a rewarding life together. Later, in a year or two, they would make their home in a large apartment above his office.

A Methodist by birth and guidance, he converted to his wife's Catholicism. He did it with ease and perhaps a bit of deviousness. After all, the papacy was a long way from Tampico, Illinois and his character and ideals had been set some twenty years before in a rural farmhouse by devout Christian grandparents and a tender, gentle mother. Little chance that any priest could improve upon this finished product! But, he was faithful and attended Mass when his duties did permit and always encouraged his children in the practice of their faith.

By the new year of 1911, had delivered so many babies, he felt himself quite an expert, until on January 7 of that year he became the father of a lovely, dark-eyed baby girl. Somehow, his expertism failed him, for this was, without doubt, the most important event ever! It called for skill and training and somehow his courage had fled, but only briefly. For to see his own child, so beautiful and perfect gave him back all the courage he needed to complete the task. An overwhelming sense of pride at what he and this wondeful woman had together accomplished filled his heart. And so a child was born, to live with and love, to nurture and grow and to comfort him in later years.

By late winter in 1914, it was apparent that war in Europe was inevitable. In August of 1914, 350 million Europeans were killing one another.

Illinois was divided in her opinions as to where the responsibility for the war lay. Most Illinoisians condemned Germany for her rape of Belgium and the stories filtered back of the new German ideology.

The decision was made by Woodrow Wilson and on April 6, 1917 the U. S. declared war against Germany.

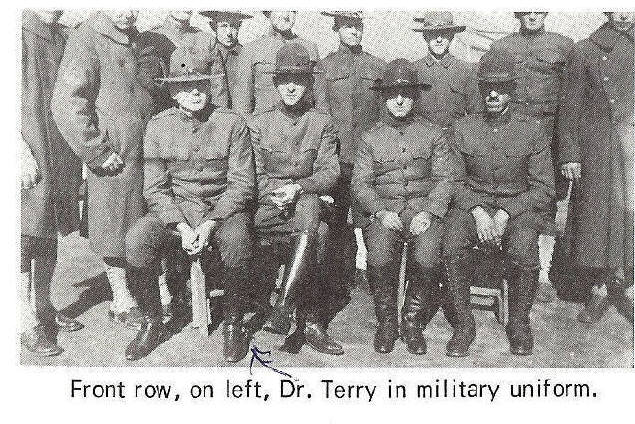

In June of 1917, Dr. Terry was drafted. He was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas as a 1st Lieutenant in the Medical Corps. In his place, a young German doctor, born in this country, but whose parents had been German immigrants, tried to handle Dr. Terry's practice.

By early Fall of 1918, the flu had reached epidemic proportions. The onset of the disease was sudden and might be accompanied by a slight sore throat. Headache, pains in the back, limbs, and joints were the first symptoms. This would be followed by a feeling of chilliniss and fever anywhere from 101 degrees to 104 degrees. Within three days, a reddened throat would evident, coughing and sneezing would begin. If there were no complications, such as pneumonia, the disease would last about a week.

Spanish Influenza had come into the country through the Eastern coast. The people of Tampico and the surrounding area did not like the new doctor. They felt he was not doing enough to halt the illness, and besides, he was a German. Public opinion can be cruel, for this young doctor did his best.

In the winter of 1918, the residents of the area got up a petition with as many signatures as they could obtain and sent it to Washington. It requested that Doctor Terry be discharged because of the pressing need for a loyal, able doctor in the area. By the spring of 1918, he was back with his own people.

But it was a sad reunion. The flu had abated, but so many of the people Dr. Terry had known and loved were gone.

The war came to an end on November 11, 1918. The troops came home. Harold Glassburn, the doctor's stepson would carry the effect of the German poison gas the rest of his life. In June of 1919, they lost their youngest son Wayne. Tuberculosis was more often that not a terminal disease.

Following World War I, there was an immigration of Belgians into theTamico countryside. Mostly farmers and wholly Catholic, they settled in the community and began to have their families. Many could not speak English and most of them began farming with little capital. When the doctor's services were needed, a collection would be taken up among these at the house to give to him. It usually amounted to a dollar or two.

His standard fee for baby cases was $25.00. Medication, such as pills or ointment, ususallly ranabout 50 cents and $1.00. To any priest or minister, he asked no fee. Wryly he had commented that he guessed that was the reason the minister always had their families while at Tampico.

In the twenties and early thirties, he averaged nearly forty babies a year. To single them out is impossible, but one went on to become Governor of California (Ronald Reagan), another an advisor to President Nixon, and many more to become doctors. His dominant characteristic was, without doubt, his dry humor.

To one lady in the agony of delivery, the whole thing seemed hopeless. Swearing and crying she screamed, "Jesus Christ, why did I ever get into this mess?" As the pain subsided, she grew quiet. But when it began again, again she shrieked, "Jesus Christ, if I ever get through this, I'll never have another!" Again the apine lessened, and she was quiet. Then, as it mounted, she again invoked the name of Jesus.

The good doctor in his quiet, dry manner said to her, "I don't believe he's here."

To another lady, having her second child, although the doctor had promised her that it would be her husband's turn this time, he related this story: "I had tis case over near Deer Grove last week where this eight-year-old boy was badly constipated. His mother was unable or unwilling to do what had to be done. Well, we gave im one enema and nothing happened, so we gave him another. The results were small. But, boy, that third one turned the tide. I tell you, honey, we finally pumped out blackberry seeds and the berry season had been over the three weeks."

So his practice flourished. The area, and whole country seemed to be prospering, but it was a prosperity built on ffalse assumptions. Business kept prices and profits high. Wages were low and labor just simply did not have enought money to buy its share of what it had helped to produce.

Fikkiwubg tge warm farners kept up their high level of production even though they no longer had to feed Europe, for the European farmers were produing again. With supply greater than demand, farmers had little money left to purchase factory products. Industry, used tomaximum production during the war made no attempt to curtail production, so they were producing more than they could sell. In addition, credit was easy to get and a great number of people piled up debts as they went into business for themselves, or they bought heavily on the installment plan.

To a country doctor, lack of funds did not signify lack of services. Dr. Terry merely shook his head at the despair around him and thanked God that he didn't have to take back all the babies that were never paid for. During these depression years, he was often paid in eggs, meat, homemade butter, and vegetables, for a course he would turn no one away. But, yet, he had drugs that had to be paid for, and,if they were not, the drug companies would merely cut off the supply.

The war years and years of depression had been strenuous years for Dr. Terry. He began to think of retirement, but he knew that doctors were hard to find in the middle thirties and he could not leave his people without a doctor.

Money was not so plentiful either since the depression had drained much of his savings. But the years had been long and hard and there had been no vacations. A few days, here, a weekend there, are pitifully few for such a man. He might never have had his dreams of retirement come true had it not been for a large inheritance from an Easter relative.

Word reached them in January of 1936, that Dr. George B. Ferguson had died and left a sizeable estate. Five cousins would share in this inheritance. Totally unprepared for this windfall, they were completely stunned by the news. The whole family had been on friendly terms with the three cousins who lived in New York. Several trips had been made back and forth in an attempt to not lose hold of family ties. Dr. Ferguson had been preceded in death by his two brothers, so therefore his closest living relatives were these cousins in Illinois.

Harry and his two sisters invested themoney in land around Tampico and Prophetstown. With financial worries behind him, he could now give serious thought to retirement. However, he still faced the problem of finding a doctor to take over his practice.

In the spring of 1936, he looked up ffrom his desk one day as a man and a woman entered the office. They introduced themselves as Dr. and Mrs. L. C. Johnson and told him they had heard he wanted to seel his practice. He smiled his wry smile, threw the keys across the desk and said, "You can have the whole damn place for $30.00."

So he and Nell went West, to California, to sea and sun and rest and leisure. They settled in Coronado and built a home. For the next few years he luxuriated in his retirement. But war was looming again in Europe. By 1939, Hitler had marched into Poland. Mary Ellen had married and her husband, A. M. Gholson, was sent overseas. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 and worry and stress once again settled over the land.

In 1943, Nell died, and Dr. Terry sold the house in California and came home to be with Marry Ellen. He enjoyed his grandchildren and was proud of them.

Death came to him gently in his sleep, symbolic of his way of life, on September 25, 1947. Many men look back at their life and question: "Why was I born?" Surely, he could look back and say: "It mattered that I lived."

To all who knew him, parent, wife, daughter, cousin, patient, friend, one word was used more ofthen than any other - gentle. For he was, indeed, a gentle, gentleman.

RELATED LINKS:

Mary Ellen Terry Gholson Obit

Marriage: Dr. Harry Terry - Nellie Aldrich Glassburn

Glassburn Family Photo Album (Nellie Aldrich Glassburn)

|